Daniel Axtell was born in Berkhamsted in 1622. He started his career as a humble grocer’s apprentice, before allying himself with the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War and playing an important role in several key battles.

Axtell was 27 years old when King Charles I was put on trial by Parliament. Charles was accused of treason and of using his power to pursue personal interests rather than for the good of the country.

Axtell’s behaviour during the trial, during which he acted as captain of the Parliamentary guard, would later come back to haunt him.

The King was found guilty and executed in front of the Banqueting House in London, after which Parliament declared a republic, known as the Commonwealth of England.

Axtell joined the ranks of the New Model Army and quickly distinguished himself, rising up to become a colonel.

Axtell was present at many key battles of the Civil War, including the siege of York and the battle of Marston Moor, during which 4,000 Royalist soldiers and 300 Parliamentarians were killed.

As well as being a staunch supporter of Parliament, Axtell was also a keen puritan. He and other puritan soldiers began preaching in churches in Oxford, despite the fact that it was illegal to preach unless you were a qualified clergyman.

Axtell later accompanied the New Model Army to Ireland in an attempt to suppress a Royalist uprising.

That year the Irish Confederate Catholics, Charles II (the exiled son of Charles I) and the English Royalists signed an alliance allowing Royalist troops to stay in Ireland. The Irish troops were put under the command of Royalist officers. Their aim was to invade England and restore the monarchy.

This was a threat which the new English Commonwealth could not ignore.

Oliver Cromwell led the Parliamentary invasion of Ireland in 1649. His hostility towards the Irish was religious as well as political, as he was strongly opposed to the Catholic Church.

After landing at Dublin, Cromwell and his army, Axtell among them, took the port towns of Drogheda and Wexford to secure logistical supply from England.

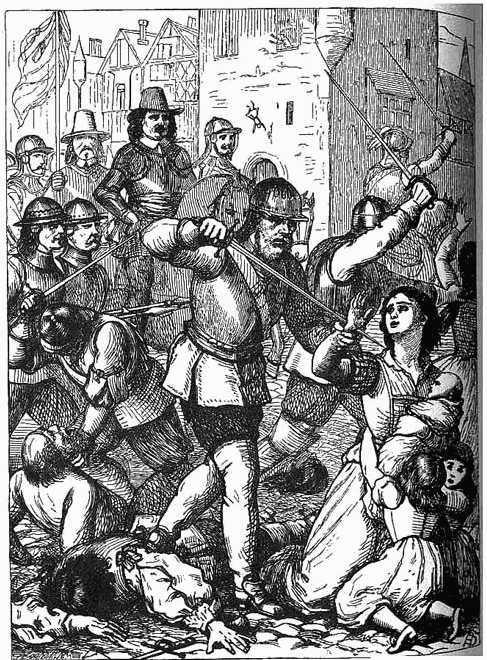

At the siege of Drogheda, Cromwell’s troops killed nearly 3,500 people, including hundreds of Catholic priests and civilians.

News of the massacre was received with horror both in Ireland and England. Stories spread of innocent people being murdered by soldiers even after they had taken shelter in a church and surrendered.

The extent of Cromwell’s brutality against the Irish has been much debated by historians. The massacre at Drogheda was just a small part of the Parliamentarians’ campaign against the Irish.

Once Cromwell had returned to England the campaign continued for another three years. The English Commissary, General Henry Ireton, began a policy of crop burning and starvation, which was responsible for up to 600,000 deaths.

The siege at Drogheda was not the only battle Daniel Axtell took part in that led to accusations of cruelty and ruthlessness against him. It is not known what part he played in these atrocities; whether he was guilty of the murder of innocents or whether he was made a scapegoat by the men who had given the orders.

In 1650, Axtell led the Parliamentarian army to victory at the battle of Meelick Island.

The battle began under cover of darkness. After hours of hand-to-hand fighting, the Parliamentarians were victorious. Several hundred Irish soldiers were killed, their weapons and equipment captured. After the conflict it was alleged that many of the Irish had been killed despite being promised clemency.

Axtell was court-martialled for this and sent back to England.

Shortly afterwards, following Oliver Cromwell’s death, the Commonwealth of England collapsed. Cromwell’s son, Richard, inherited the title of Lord Protector, but proved inept at politics and resigned. The Commonwealth collapsed without an effective leader and the exiled Charles II was invited back to act as king.

During this time, Axtell returned briefly to Ireland as a colonel. Shortly afterwards, however, he was sent back to England.

He remained a staunch Parliamentarian, a firm believer in the ‘Good Old Cause’, the name given to Parliament’s fight against the Royalists by soldiers of the New Model Army.

Axtell’s attempts to oppose the restoration of the monarchy were unsuccessful and he was subsequently arrested as a traitor.

In the end it was not Axtell’s alleged ruthlessness as a soldier that led to his downfall, but his loyalty to Parliament and his hatred of the crown.

Axtell was arraigned for treason for his actions during King Charles I’s trial. His defence was that he was only obeying orders at the trial, but several witnesses testified that he had behaved rudely towards the King, and had jeered at Charles when he tried to speak.

The court declared that, even if Axtell had been obeying orders, it was no excuse for his traitorous behaviour.

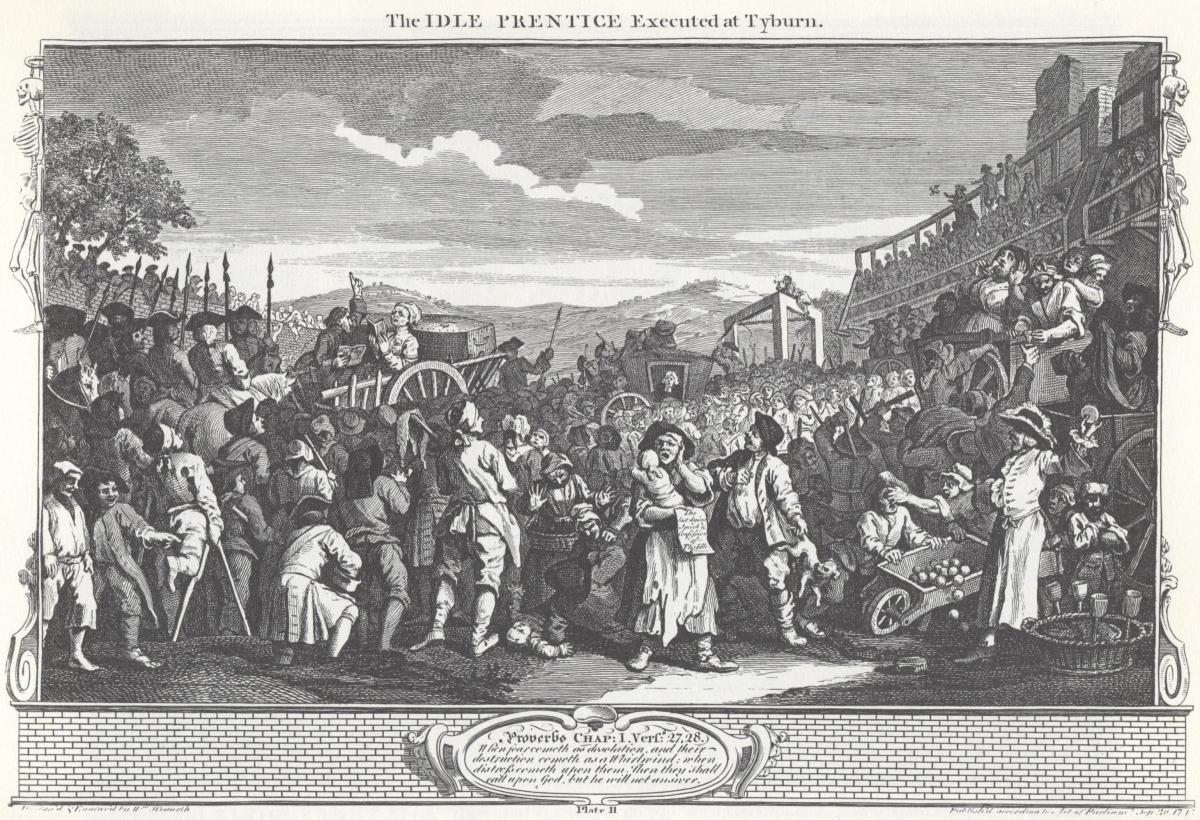

On October 19, 1660, Daniel Axtell was executed by being hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn. His head was impaled on a spike at Westminster Hall.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel