The Watford Observer has again teamed up with its friends at The Watford Treasury to share stories from previous issues.

Geoff Wicken looks back on what at that time was the biggest game Watford had ever seen, and one which would be talked about for years.

‘Never before in the history of the club has there been such excitement and enthusiasm in Watford since it was known that the Blues had been drawn at home against Manchester United, the favourites for the cup.’

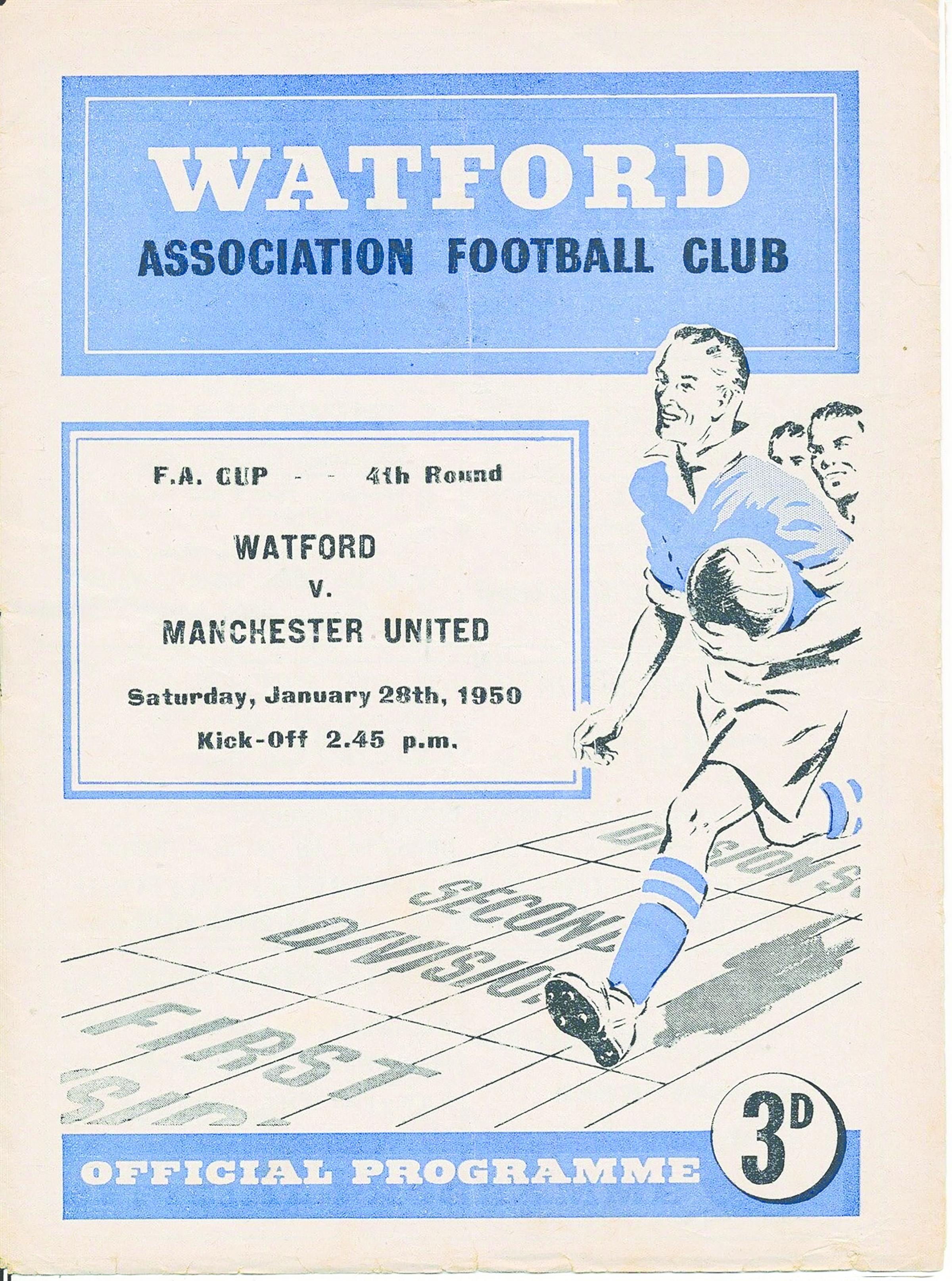

So wrote the match programme for the FA Cup Fourth Round game at Vicarage Road on January 28, 1950. Amid today’s world of media and Premier League hyperbole, it sometimes seems that every game Watford play is a big game. And if it’s not a big game, that’s only because it’s huge. Back then things were different. When Watford were drawn against Manchester United in the 1949/50 FA Cup, the description was genuinely merited. Very few previous games at Vicarage Road, or Cassio Road earlier, could have been defined as ‘big’.

After joining the Football League in 1920 along with the rest of the Southern League clubs, Watford meandered along in the still waters of Division 3 South. The club had little success, but the structure of the Football League – imposed by the mostly northern Division 1 and 2 clubs as a condition of the Southern League’s accession in 1920 – made that almost certain.

Only the champions from the 22 clubs went up each season, so by design your chances of promotion were slim. And if you didn’t get off to a good start they would be pretty much over by November. Nor was there much jeopardy at the other end of the division. The bottom two clubs were obliged to seek re-election at the Football League’s annual meeting, but in the 23 years of Division 3 South’s existence up to 1949/50 only four clubs had been ejected. Clearly it took a lot to lose your place – although, given that three of those four were Aberdare Athletic, Merthyr Town and Newport County, one wonders whether the opportunity to cut down on lengthy away trips to Wales was a motivating factor for those casting their votes.

Watford to that point had only come close to leaving Division 3 South on two occasions. The club survived the ignominy of applying for re-election in 1926/27 (the year in which Aberdare departed) and in 1937/38 finished in fourth place, only three points behind champions Millwall. The Division 3 South experience was stable, but repetitive. In most seasons, you would play 20 of the 21 clubs you had played the season before.

So the FA Cup was often the only chance of excitement. This was one reason for its popularity: the hope of a good run, or being drawn against top opposition on your own patch. But eye-catching ties at home to storied opponents didn’t come around frequently. The probability, if you were to calculate it, was about one in 20. That’s because for clubs entering the FA Cup in the first round, the odds of winning two games and going through to the third round were – assuming rough parity between all teams involved at that stage – one in four. After that, your chance of being drawn at home to a Division 1 side was little better than a further one in six. Combining these probabilities, you would conclude that such a fixture might happen every 20 years or so.

Sure enough, this had been Watford’s experience. In those first 23 Football League seasons, only once had a Division 1 club been drawn to play at Vicarage Road: Newcastle United in the 1923/24 Fifth Round, whilst Cardiff City had also visited for a replay in 1922/23. Far more likely was an exit in the first couple of rounds – sometimes an embarrassing one, such as Watford’s defeat at Leytonstone in 1948/49. So Manchester United’s visit the following year was the first home cup tie against Division 1 opponents in a generation.

Watford had overcome non-league opposition in the first two rounds, in the form of Bromley and Netherfield. The Third Round brought a home tie against Second Division Preston North End, and a 2-2 draw before a 25,000 crowd meant a replay at Deepdale. Dave Thomas scored the only goal, and the anticipation began.

Manchester United were unquestionably one of the top teams in the country. Players such as Jack Rowley, Stan Pearson, Charlie Mitten, Johnny Carey and John Aston were household names in what was the first of the teams put together by manager Matt Busby. They had won the FA Cup in 1947/48, and been Football League runners-up in both that year and 1948/49. In January 1950 they again stood in second place in Division 1. Watford meanwhile were enjoying a reasonable league season, tenth in Division 3 South at that point.

The game was eagerly anticipated. Watford fan John Pipe recalls the demand for tickets. He said: “There was great excitement in the town, because we were minnows then, and a lot of clamour for tickets. A lot of schoolboys – me included – played hookey on the afternoon they went on sale. My mate and I went down and stood in the queue. When we got there we were about 200th in the queue, and we stood there waiting and holding the places until our dads came from work. There were kids from other local schools too and it was good fun, but we never got told off – because of the atmosphere I suppose.”

The Watford Observer commissioned Aero Films of Elstree to send an aerial photographer up in a plane above Vicarage Road. There was national interest too: ‘The Sporting Mirror’ magazine featured Dave Thomas on its front cover prior to the game, while the front page of ‘Sports Reporter’ pictured the whole Watford team.

Watford produced a 12-page programme for the game

For the occasion Watford increased the match programme to 12 pages and introduced a new-style cover design. Inside, it set the scene elegantly: ‘The Blues realise the enormity of their task today, but are quietly confident that they will put up a good show. They know that Preston, despite lavish expenditure on players, were a team in the experimental stage, whereas the United are already a seasoned combination, and reckoned by many critics to be the finest side in the country. Well, we are privileged and delighted to welcome them to Vicarage Road this afternoon and hope to have a real football treat.’

The crowd of more than 32,000, which included around 5,000 away fans, comfortably beat the previous Vicarage Road record of 27,000. The Watford Observer reported that several thousand more might have been accommodated, commenting that ‘the fact that the boys were allowed inside the arena helped to make the arrangements a success.’ John Pipe was one of those who saw the game at close hand: “I was one of the kids who was passed down over the heads of the crowd down to the front. I watched from the dog track, which was completely filled.”

Judging from the match reports in the press and Pathé News (there’s a short piece of footage on YouTube) the game itself was a classic tale of the plucky underdogs putting up a good show, but failing to score, with the favourites then grabbing a late winner within the last 90 seconds. The Watford Observer report describes Jack Rowley’s goal, the only one of the game, as ‘stark tragedy for the local side. It ended an inspiring cup run, it sent the hopes of the Blues’ supporters crashing to earth, and it did something more. In plain, simple language, it robbed the Blues of their just desserts, for if ever a team earned the right to a second crack it was this gallant Watford side.’ The national press too was highly complimentary. ‘Oh, Mr Busby, what a lucky day!’ wrote the Daily Mirror. ‘For 89 minutes Jack was as good as his master, and at times, in fact, looked very much better’ said Reynolds News.

The programme for Watford’s following home match, against Walsall, didn’t hold back: ‘Few who saw that thrill-packed game a fortnight ago are likely to forget it for many years to come. Even the staunchest and most optimistic Blue supporter must have had misgivings that his team could cope with such an international-studded combination as the United. But the players rose to the occasion, and proved that, given the chance, they could produce as crisp and intelligent football as any in the land.’

United might have taken the lead earlier. Ten minutes into the second half they were awarded a penalty when the ball struck Tommy Eggleston’s hands as he was protecting his face. Left-winger Mitten sent the kick way wide of the goal, as John Pipe describes: “His penalty shot almost hit the corner flag. We just couldn’t believe anyone could miss a penalty by that much! The ball ended up on the steps that used to run down from the turnstiles in the top corner of the Vicarage Road end.”

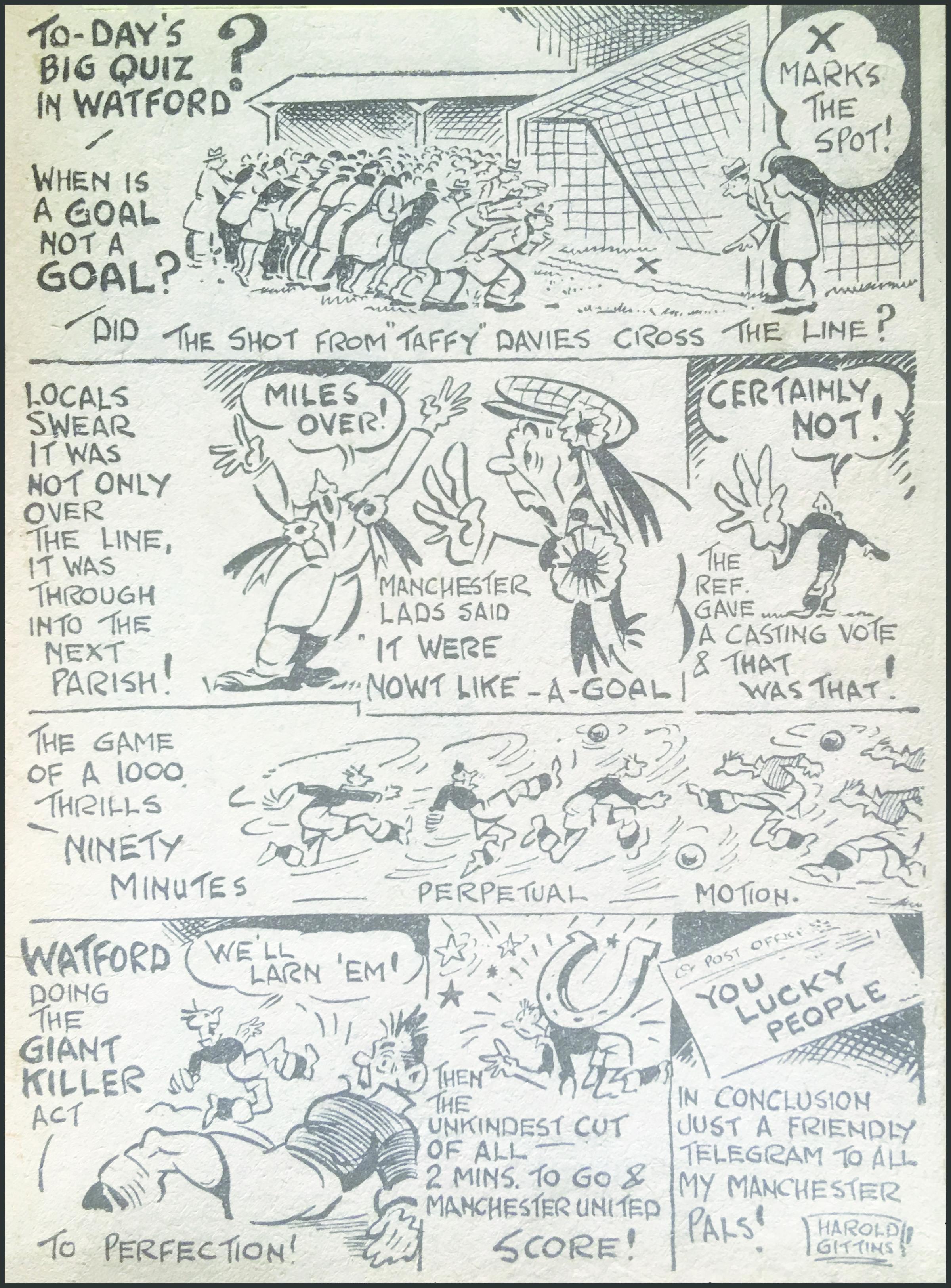

The Watford Observer published a cartoon reflecting on Taffy Davies' goal that was disallowed

But the most controversial moment had come earlier. Many in the ground believed that Watford’s Taffy Davies scored a legitimate goal that wasn’t given. As the programme for the Walsall match described it: ‘Lancaster was well and truly beaten when ten minutes before the interval a finely placed cross from Taffy Davies sailed over his outstretched arms and, so it appeared, well over the goal line, before Aston with a do or die effort headed the ball out of the goal. Fierce controversy has arisen as to whether this was a goal or not, and though the Blues forwards and spectators in a position to judge were convinced that it was, the referee decreed otherwise and that was that.’

This was the talking point not just immediately after the match, but long afterwards too among Watford supporters – whose football-watching experience returned to the normal mundanity of life in Division 3 South. John Pipe puts it in a nutshell: “It was talked about for years. That, along with winning at Preston beforehand, was our only highlight.” Even 19 years later in 1969, discussion of it formed part of the build-up when Manchester United returned to Vicarage Road for a Fourth Round FA Cup replay.

As it was, rather than this being an indicator that success was just around the corner, it proved an isolated highlight. Watford were to disappoint their fans for most of the next ten years. The very next season, 1950/51, saw the club finish second-bottom and have to apply for re-election again, and there were mostly poor league positions through the rest of the 1950s.

Only in 1959/60 did things change. With Watford in Division 4 following the league reconstruction, that season saw the club’s first-ever Football League promotion. It was also the next time that a First Division club – Birmingham City – was drawn to play at Vicarage Road in the FA Cup. And for the first time at Vicarage Road, Watford beat Division 1 opponents. It had taken another decade, but finally Watford achieved the result many fans felt they had deserved against Manchester United ten years earlier.

You can buy all issues of the Watford Treasury at thewatfordtreasury.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel